Let's examine this relationship more closely by copying this nerd's homework

"New Urbanism and Nazi Germany : a comparative study of neotraditional community design and the Third Reich". https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7548&context=utk_gradthes

spoiler

the writer lets the New Urbanists completely off the hook for their obvious cryptofascism (Western academics understand the historical political context of ideas Challenge - Impossible)

Welcome To Seaside

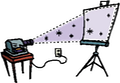

Seaside, Florida, widely hailed as the genesis of new urbanism, began in 1946, when urban wealth encountered the rural South. In that year a Birmingham department store magnate, J .S. Smolian, purchased eighty acres of remote, undeveloped beachfront property on the Florida Panhandle. He paid a princely one hundred dollars per acre for the scrub and weed-filled parcel. Pundits, even within his own family, deemed him a fool for the purchase. Yet Smolian was unfazed, for he had a vision for this property. It would become "Dreamland Heights," a summer vacation retreat for his six hundred employees. Smolian's dream, however, was never realized. Instead the land lay largely vacant and undeveloped for much of the next thirty years

in 1978, Smolian's grandson, Robert Davis, inherited the sandy lot

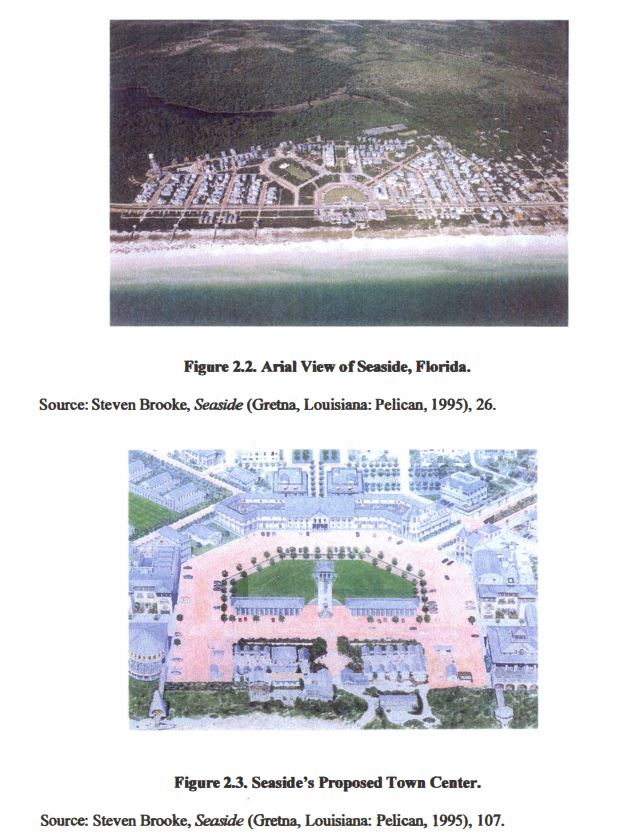

Robert Davis, a Harvard-educated real estate developer, was the at the forefront of a new community design movement, known as "new urbanism."

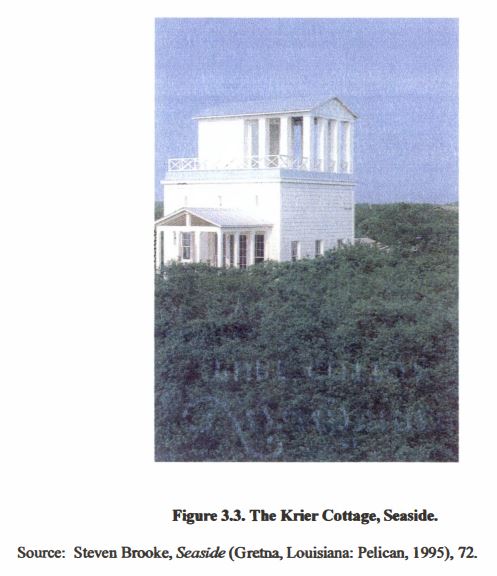

Davis, educated at Antioch College and Harvard, established himself as an innovative builder in the Miami suburb of Coconut Grove during the 1970s. About the same time, he became exposed to the writings and theories of Leon Krier

Called the "Le Corbusier of our day," Krier emerged during the 1970s as the most outspoken critic of modernism. "The principal aim of industrial civilization has been to transform the most beautiful of cities into the worst enemies of man." "Industrialization," in his view, has "only facilitated centralization of capital and of political power" while destroying "those cities and landscapes which had been the result of thousands of years of human labor." Rejecting the "obsessive emptiness" and "confused formulations" of modern architecture, Krier argued that "the form and quality of urban space can only be verified by historical models." The architect disdains modern structures and techniques, including curtain walls, flat roofs, and HV AC systems, in favor of traditional building styles and materials. Thus, among Krier's followers, neoclassicism and the "ageless mandala of the Roman camp" have become the model for community design and serve as "reminder[s] of the Empire's lasting hold, its beneficence, order, and its splendor."15

Krier also lashed out at suburban growth, which he blamed for the rise of the "industrial anti-city." "Suburban sprawl," he argued, "is based on a marriage of convenience and, lacking any roots, it repudiates heritage, traditions, and cultures." In Krier' s eyes, the suburb is an insidious creature which "wants to conquer the world because it cannot be at peace with itself."

"The suburb without a city is like a cancer without a body," he wrote, adding:

"A suburb built 1 00 miles away from a city will do everything to attack its victim: it will erect vast infrastructures and mobilize colossal machines in such a manner as to realize its objectives of destruction. The suburb strangles the city surrounding it and kills the city, tearing out its heart. A suburb can only survive, it cannot live. It can survive like a parasite, consuming both city and countryside. No city and no countryside, however rich and fertile, can survive besieged by a suburb."16

Krier also hurled invectives at modem planning and zoning. A "good plan," according to Krier, "is both of a formal and moral nature" and "fixes once and for all" building types, public spaces, and land uses. Zoning, he believes, "mobilizes" these "immovable and fixed values." It is "an instrument of industrial monopoly planning and is not democratic but totalitarian." The result is "simply a sum of buildings and functions" with no "body and soul" and the destruction of "Pre-industrial urban communities, of urban democracy and culture." "If we start dismembering a human body," he wrote, "we slaughter the individual," adding, "that is exactly what zoning does to the body of the city." Krier argued that zoned cities such as New York and Los Angeles were not, in fact, cities but mere "agglomeration[s] of buildings." "Venice," however, with its traditional design elements, "is a city and so it will remain even if inhabited by cats and fish." The architect then concluded with a final, classical pronouncement: "Just as Carthage was the first enemy of Rome, I have yet to repeat again: 'Ceterum censeo zoning essere deletium'." 11

7"In my opinion, Zoning must be destroyed." Krier's declaration is an allusion to Cato the Elder' s famous dictum "Ceterum censeo Carthago essere deletium (In my opinion, Carthage must be destroyed.)." Interestingly, Cato, also known as Cato the Censor, was widely known for his outspoken opposition to new or nontraditional ideas. Krier, Houses, Places, Cities, 32-33, 102, 104-105.

Krier also waxed nostagically for traditional, pre-industrial urban centers. Such cities, he believed, are characterized by their densities and compactness. The major definer of such communities, he argued, are pedestrian distances. This primacy of foot traffic encouraged the development of"cities within the city." The urban quarter, which contains "all daily functions of urban life," becomes the crucial element of Krier' s ideal city. These neighborhoods, "not exceeding 35 hectares (86 acres) and 15,000 inhabitants" represent, he contends, the optimal size for "rural or urban communities." In evaluating these quarters, the architect focused almost exclusively on examples from European cities. In fact, Krier's arguments were decidedly Eurocentric. To him, the continental city was "a place of privileges, civil rights, and liberties." In contrast, the American city, characterized by low density expansion, was "a place of damnation, but necessary for survival. " 18

Krier' s angry rhetoric was more than an assault against planning. It was also a call for a radical restructuring of urban society. "Reconstruction" became the rallying cry for Krier and his followers. "The project which our generation must elaborate has to fight the destruction of urban society on all levels, cultural, political, economic." Architects, he commands, must "refuse" to "comply with the deficiencies of existing legislation and budgeting" and "recognize the value of pre-industrial cities." Krier's mission reflects more than a quest for urban renewal, it is an attempt to reverse the course of modernity and return to an "artisanal" order. "The enormous work which awaits our generation in repairing the damages and destructions of the last thirty years must be undertaken in a perspective of material permanence," he wrote, adding "Only with this project of reconstruction can we redefine our role as architects and establish the Authority of Architecture as Art [sic]."19'

In the late 1970s, during the final years of Albert Speer's life, a small cadre of architects undertook a program to rehabilitate the image of Hitler's former architect and redeem his creative legacy. At the forefront of this movement was Leon Krier. the guru of new urbanism and high priest of neotraditional design. In an essay on Speer, Krier praised the German's body of work as "the architecture of desire." Although he reproached Speer for "his unrepenting belief in industrial civiliz.ation" Krier lavished praise on the ex-Nazi's classical designs, which he feels were "condemned by the Nuremberg Tribunal to an even heavier sentence" than their creator.

the real loser of WW2 was pretend Roman columns

Speer, he believes, was "a born form-giver ... graced by an extraordinary ability to think in four dimensions, to conceive structures in space and time, in parts and total."

cubebrained Speer?

Because of this, Krier believes Speer was able "to bring almost any problem to its implacable solution, brushing aside technical and moral objections." Speer's, downfall, in Krier's mind was not aligning himself with fascism, but rather believing "that a powerful and prestigious cultural elite, upholding the highest standards of style and good taste, would be able to impose quality on industrial mass production."1

1Krier goes on to remark "Auschwitz - Birkenau and Los Angeles are children of the same parents. They are reifications of social place less ness, of the incapacity to give human work and commonwealth dignified and pleasing forms."

lmao let him cook...

Later, Krier also recalls the "good sides" of "Hitler's socialism," including the Reich's "advanced social legislation," the "astonishing development of German civic spirit," and the Nazi's "admirable love" for "the landscape and for classical architecture." Leon Krier, ed., Albert Speer, Architecture: 1932- 194 2 (Brussels: Aux Archives D' Architecture Modeme, 1985), 217, 222, 227.

Correction, do NOT let him cook

(Continued below)

he's not being literal, right??

he's not being literal, right?? :

:

(pointing) this is where the work camp will go

(pointing) this is where the work camp will go