this post was submitted on 30 Oct 2024

71 points (80.9% liked)

Atheist Memes

5578 readers

263 users here now

About

A community for the most based memes from atheists, agnostics, antitheists, and skeptics.

Rules

-

No Pro-Religious or Anti-Atheist Content.

-

No Unrelated Content. All posts must be memes related to the topic of atheism and/or religion.

-

No bigotry.

-

Attack ideas not people.

-

Spammers and trolls will be instantly banned no exceptions.

-

No False Reporting

-

NSFW posts must be marked as such.

Resources

International Suicide Hotlines

Non Religious Organizations

Freedom From Religion Foundation

Ex-theist Communities

Other Similar Communities

!religiouscringe@midwest.social

founded 1 year ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

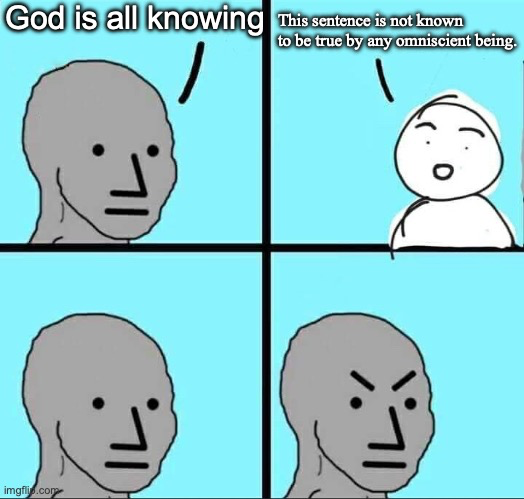

I'm not sure how that's moving goalposts. The two issues seem fundamentally connected.

I don't think it's an issue of capability, god is supposed to be capable of all things, pain free world included. It's a question more of will.

God could have willed the world another way, or not at all, and still have been completely satisfied. But he has chosen this way because it's his will and god tells us it's good. If he regards his will as good, why would he change it to another?

That's what I mean by moving the goalposts. You just shifted it to support all-knowing and all-powerful by unchecking all-good. If god could have willed our world another way and chose not to, he created and continues to facilitate evil, and is thus malevolent.

I understand what you're saying, but respectively I didn't uncheck the "all good" box. I pointed out that there are two definitions of "good" in play and so the statement "god is all good" is meaningless without further inspection.

If we use god's definition of good then the "all good" remains checked because god gets to define goodness itself and whether or not he wants pain to be necessary to achieve good.

On the other hand if we use our sense of good, then the question is begged because it establishes a hierarchy of values that does not have god at the top and then concludes god is a contradiction. But this is inevitable from our assumptions that there is such a thing as an infinite moral authority yet there is also our moral authority which is better.

In short, I think the Epicurean statement is a pithy way of saying god fails our human standards (which is true, by the way). But then religion doesn't claim god follows our human standards in the first place, so it all seems a bit pedestrian.

Redefining 'good' to whatever it is you speculate may be cooking in Zeus's noggin isn't going to dodge the Epicurian paradox, it just changes it to god can't be all three of 1) all-powerful, 2) all-knowing, 3) all-whatever-the-fuck-word-god-chooses-to-use-to-label-the-concept-of-the-thing-we-call-'good'.

That's like arguing that the thing you're looking at right now isn't a screen, because maybe god calls it a chipmunk instead.

This isn't about labels, but the substance of the thing itself

god can be "all good" if the definition is different to the one you or Epicurus is using.

To restate what I said above, all Epicurus is really saying is "god can't be all powerful, all knowing and fully good according to Epicurus' definition of good."

For the Epicurean paradox to work one has to assume that his definition of good is both correct and universal. That's all I'm pointing out.

I'm not trying to needlessly spilt hairs; abrahamic religions are quite up front that god's idea of goodness is different to 'human goodness'.

So whether or not the statement makes sense depends entirely on whose concept of goodness you assume at the outset.