this post was submitted on 14 Sep 2024

20 points (95.5% liked)

Weather and Meteorology

174 readers

1 users here now

Hope to expand on this later. A community for discussing the weather (very UK), amateur meteorology, and moaning it's too hot/cold/wet/dry/mild.

founded 1 year ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

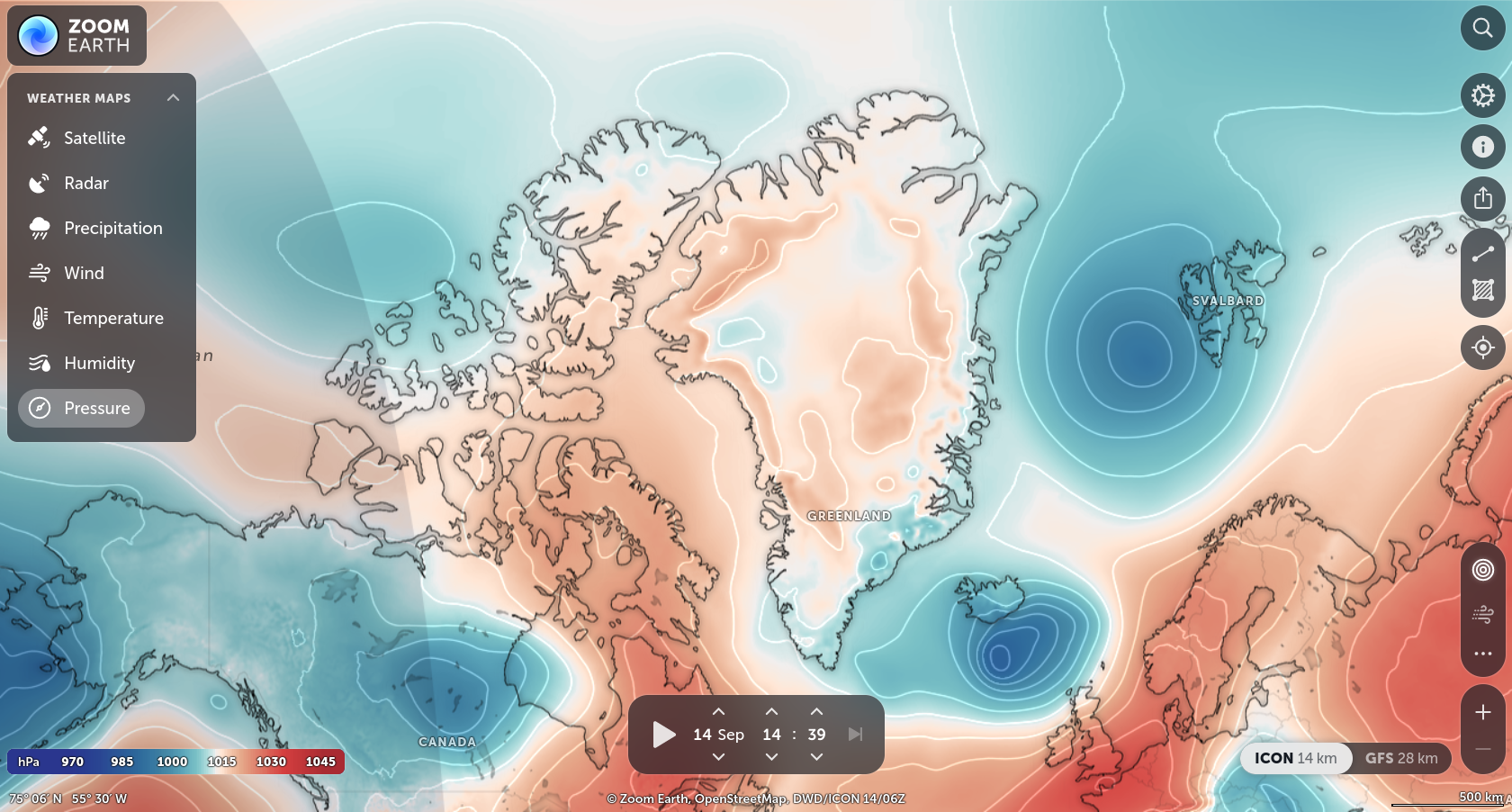

The way it is taught in many Earth Science text books, is that if you have two similar volumes of air, but the first is colder than the second, the first will have a higher density, and therefore a larger mass, and therefore a higher air pressure (e.g. at the surface).

Following this logic, you expect higher pressure in colder areas, as long as the volume of air (the height of the air column) is the same. I think the answer to my question has to do with the latter: the atmosphere is less thick at the poles. As a result, despite the much lower temperatures, the air pressure at the poles is generally lower than (for example) at the subtropical highs.

the complication is that in meteorology, the volume of gas does not remain the same! if you're changing the mass, temperature, density, and pressure of a parcel of air, you definitely can't assume that the volume is constant

it's good to use a different ideal gas equation, instead of PV = nRT (pressure x volume = n * R * Temperature)

we meteorologists tend to stick to unit masses, and use: Pressure = density ×R×T, instead

i.e. when temperature decreases, pressure decreases

Also, the formula Pressure = density x R x T doesn't show that pressure decreases as temperature decreases, since a temperature decrease also increase the density?

But clearly, on a global scale, the opposite is true? As in, for example, the ITCZ is located at the subsolar point, where the planet receives the most irradiation, and this is an area of low pressure (and convection)? High temperatures -> low pressure.

The ITCZ is an interesting case to use here! You're right that it's the thermal equator and has low pressure, but you've gotta consider convection and wind direction too (i.e. the whole Hadley cell). Convection (caused by solar heating) causes low pressure too, and pressure is often relative.

When you're thinking about stuff on a global scale you've always gotta consider the global atmospheric circulation

There's a lot of good explanation in the link I sent - it's tricky trying to consider all the variables together, but I would say that variations in density (latitudinally, at least - unless you want to start talking about hydrostatic balance!) doesn't account for the variation in pressure or temperature.