Just Tax Land

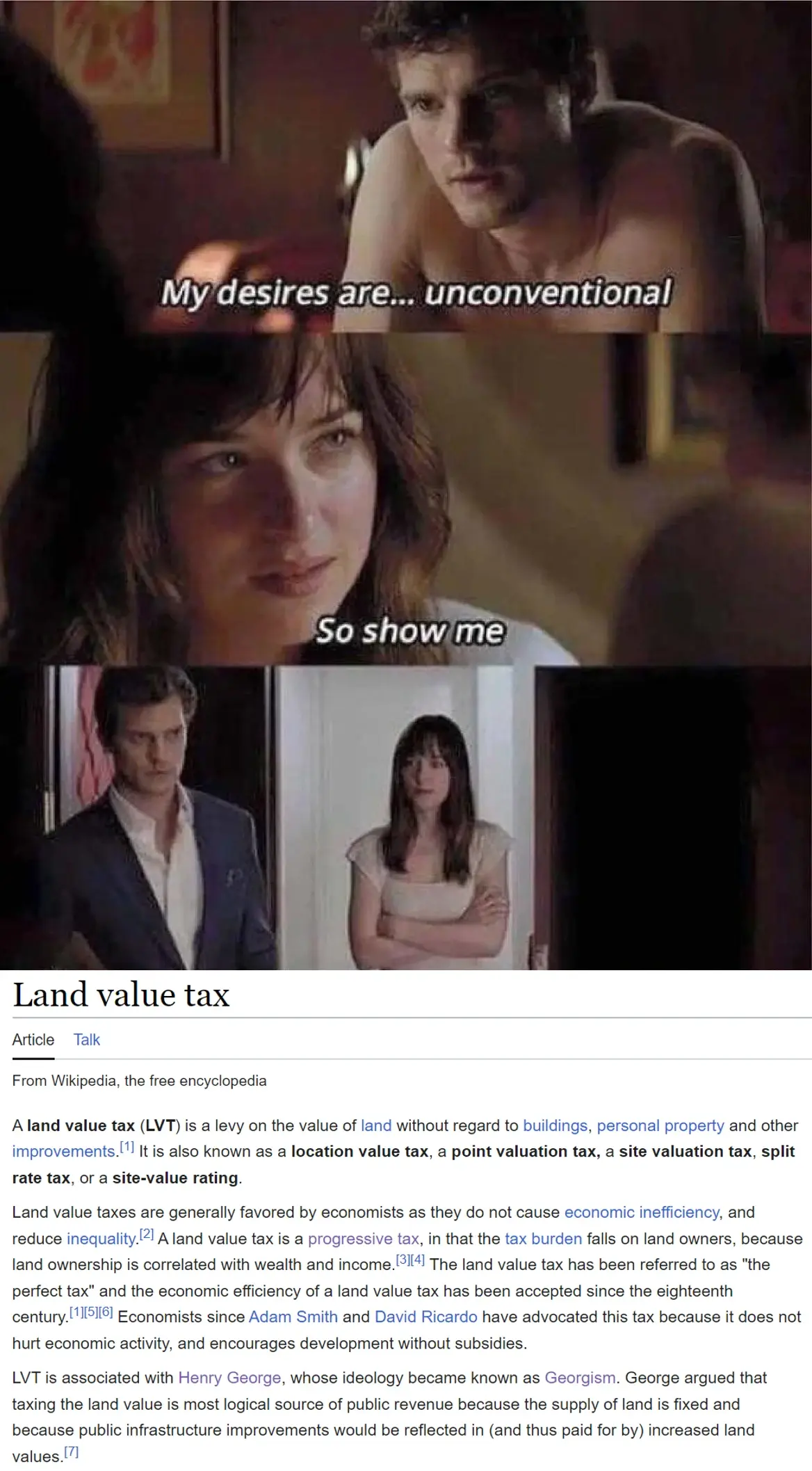

Land Value Tax

From Wikipedia:

A land value tax (LVT) is a levy on the value of land without regard to buildings, personal property and other improvements.[1] It is also known as a location value tax, a point valuation tax, a site valuation tax, split rate tax, or a site-value rating.

Land value taxes are generally favored by economists as they do not cause economic inefficiency, and reduce inequality.[2] A land value tax is a progressive tax, in that the tax burden falls on land owners, because land ownership is correlated with wealth and income.[3][4] The land value tax has been referred to as "the perfect tax" and the economic efficiency of a land value tax has been accepted since the eighteenth century.[1][5][6]

...

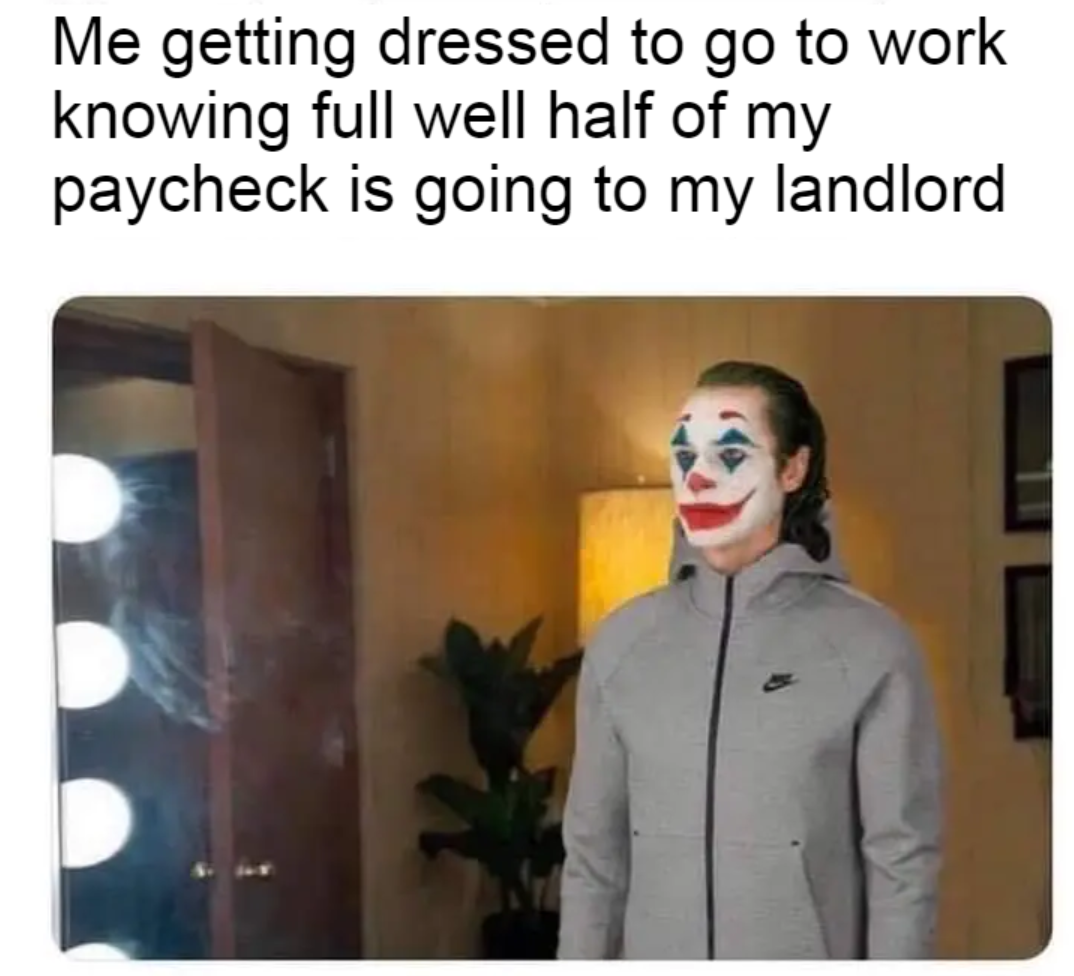

Most taxes distort economic decisions and discourage beneficial economic activity.[14] For example, property taxes discourage construction, maintenance, and repair because taxes increase with improvements. LVT is not based on how land is used. Because the supply of land is essentially fixed, land rents depend on what tenants are prepared to pay, rather than on landlord expenses. Thus landlords cannot pass LVT to tenants, who would move or rent smaller spaces before absorbing increased rent.[15]

...

LVT's efficiency has been observed in practice.[18] Fred Foldvary stated that LVT discourages speculative land holding because the tax reflects changes in land value (up and down), encouraging landowners to develop or sell vacant/underused plots in high demand. Foldvary claimed that LVT increases investment in dilapidated inner city areas because improvements don't cause tax increases. This in turn reduces the incentive to build on remote sites and so reduces urban sprawl.[19] For example, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania's LVT has operated since 1975. This policy was credited by mayor Stephen R. Reed with reducing the number of vacant downtown structures from around 4,200 in 1982 to fewer than 500.[20]

LVT is arguably an ecotax because it discourages the waste of prime locations, which are a finite resource.[21][22][23] Many urban planners claim that LVT is an effective method to promote transit-oriented development.[24][25]

Georgism

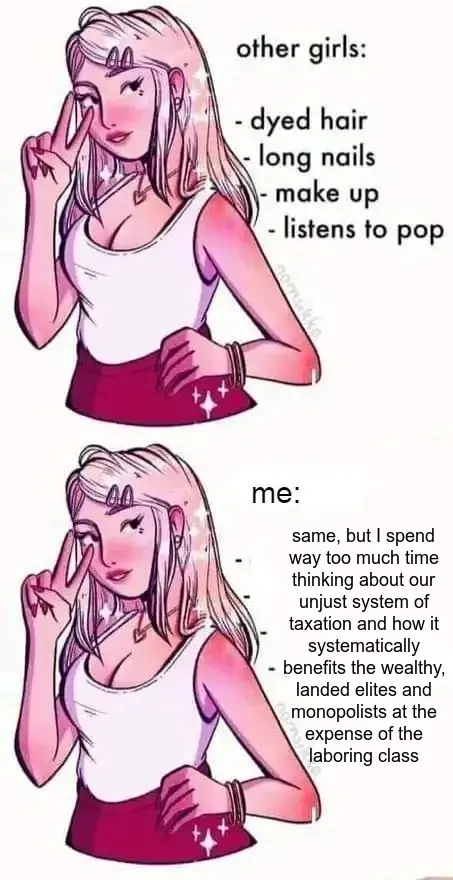

Georgism (otherwise known as geoism) is an economic philosophy holding that the economic value derived from land, including natural resources and natural opportunities, should belong equally to all residents of a community, but that people own the value that they create themselves.

Most Georgists support:

- A broad-based land value taxation scheme, either to mostly or entirely replace existing harmful taxes on income, consumption, and corporations.

- The social redistribution of this revenue either directly, through a Citizens' Dividend, or indirectly, through government programs, to citizens.

- Some (but not all) forms of market intervention by the state.

- The abolition of tariffs, quotas, patents, and other barriers to trade and commerce.

The overall goal of Georgism can be summarized as follows: to eliminate rent-seeking and monopolism so that the economy can be free, fair, efficient, and prosperous for all.

The Georgist paradigm crosses the left-right political divide. This means that there are statist, anarchist, progressive, and conservative Georgists.

Posting Guidelines

In the absence of a flair system on lemmy yet, let's try to make it easier to scan through posts by type in here by using tags:

- [meta] for discussions/suggestions about this community itself

- [article] for news articles

- [blog] for any blog-style content

- [video] for video resources

- [academic] for academic studies and sources

- [discussion] for text post questions, rants, and/or discussions

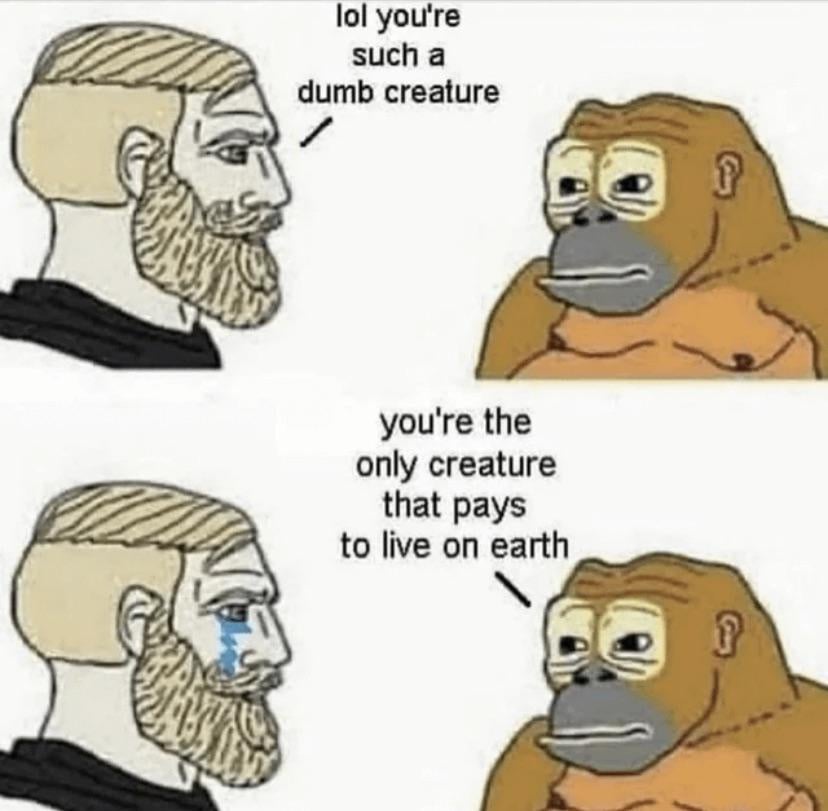

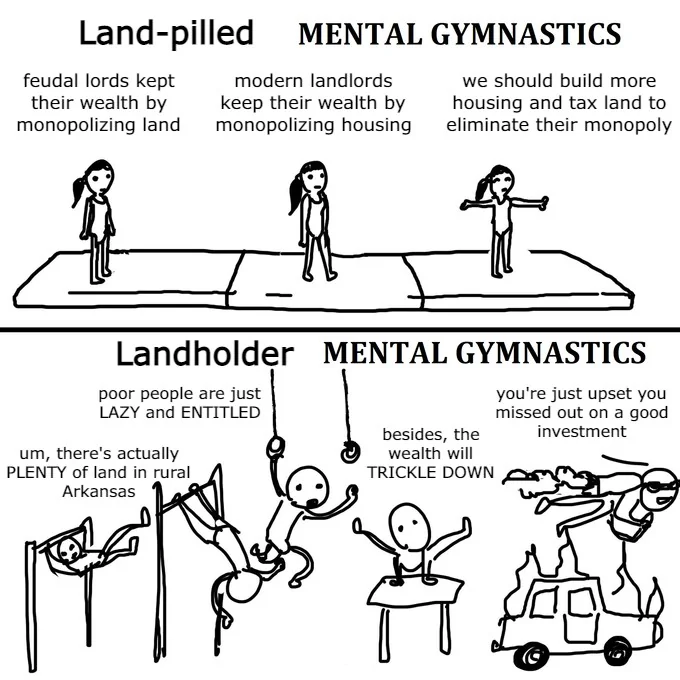

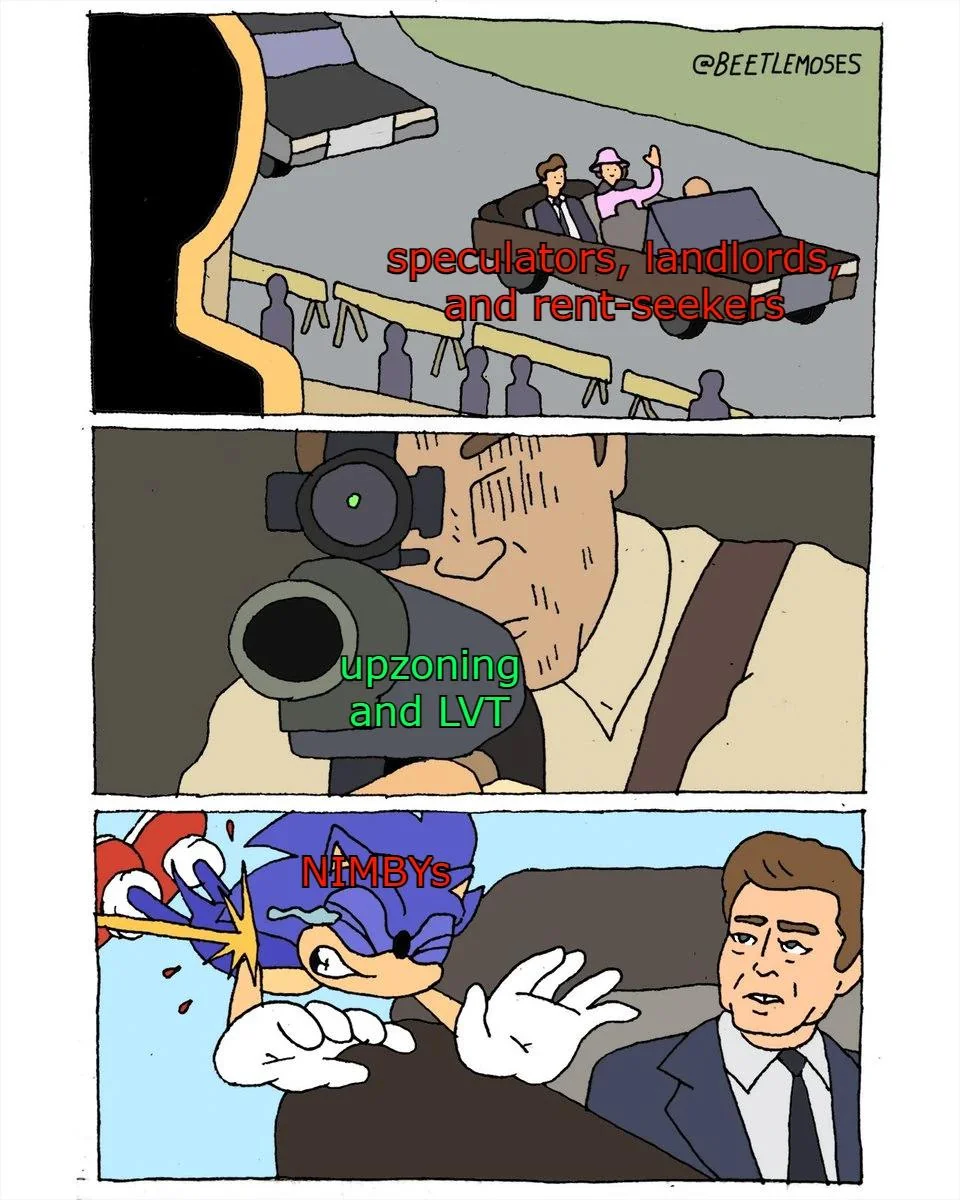

- [meme] for memes

- [image] for any non-meme images

- [misc] for anything that doesn't fall cleanly into any of the other categories

Additionally, it is preferred (although not mandatory) to post a brief submission statement in the body of link posts. This is just to give a brief summary and/or description of why you think it's relevant here. Hopefully this will encourage more discussion in this community.